Not many years before Jesus was born, the Roman poet Virgil died. In the decade preceding his death, Virgil was writing the Aeneid, a poem that has been called the national epic of the Roman empire. In the second half of the epic, Virgil brings his skill as storyteller to the subject of anger, revenge, violence, and bloody warfare.

Not many years before Jesus was born, the Roman poet Virgil died. In the decade preceding his death, Virgil was writing the Aeneid, a poem that has been called the national epic of the Roman empire. In the second half of the epic, Virgil brings his skill as storyteller to the subject of anger, revenge, violence, and bloody warfare.

In a visionary book that explores the limits of violence and war, and skillfully shows the benefits of peaceful change, the late Jonathan Schell puts his finger into history at the time of Virgil and Christ to write about two coexisting yet conflicting traditions. One is worldly and violent, Schell writes. It is “a system, at its best, of standing up for principle with force, right with might; at its worst, of plunder, exploitation, and massacre.” This tradition, Schell notes, was exemplified by Virgil in the Aeneid, whose opening words set the stage: “Of arms, and the man I sing.”

Not long after Virgil was writing “Of arms, and the man I sing,” Jesus, Shell writes, was speaking words that would become much better known: “Put up thy sword, for all who draw the sword will die by the sword.” And “it was in the heat and fury of [a] bloody altercation, not from the quiet of a philosopher’s study,” that Jesus said this. Jesus, Schell continues, “sang of the man without arms,” and since then “the two conflicting traditions – one sanctioning violence, the other forbidding it – have coexisted,” each retaining its power in spite of the other. But, he concludes, “Force can only lead to more force, not to peace. Only a turn to structures of cooperative power can offer hope” (The Unconquerable World: Power, Nonviolence, and the Will of the People).

I was disturbingly reminded of the diametric tug of these two perennial traditions upon the human heart when I watched a television interview of Christian author and speaker Rick Joyner. For those unfamiliar with the name, Rick Joyner founded MorningStar Ministries in 1985 and became fairly well known within charismatic Christian circles for his books and for teaching about his many dreams and visions, which he claimed were prophetic. In 2004, MorningStar purchased part of the former Heritage USA complex, once owned by Jim Bakker and PTL, in North Carolina. Bakker and Joyner have been close friends for decades and it was Bakker’s interview of Joyner that I listened to.

The interview aired two on September 11, 2020, on “The Jim Bakker Show” and ran for nearly an hour. It included much mutual back-patting that lead to this question from Baker: “Where are we in the prophetic time line?” What follows is a long and disturbing conversation in which Joyner mentions a dream he had in 2018 about what he calls a “civil war” being fought in the streets of American cities.

As the interview progresses, Joyner sounds more closely allied with Virgil’s violent warrior Aeneas than with the gospel’s peaceable Jesus. Joyner asserts that America is already in that civil war and that followers of Jesus need to be prepared to take up arms and fight in it. Although Joyner briefly mentions that he “hates to say this,” and that “some people don’t even want to comprehend” it, any fellow feeling meant dissipates before his contention that followers of Jesus get out their guns and join in with those he calls the “good” militias to fight bloody battles in the streets of their cities against those whom he identifies as “the bad people.”

One cannot listen to the second half of the interview and conclude anything other than that Joyner is talking about followers of Jesus getting their guns and participating in a violent civil war. That is the plain message, which Joyner loads with comments such as: “we’re already into it”; “we’re gonna have to fight for what we believe”; “it’s time to choose sides”; “we’ve gotta fight to win.”

Followers of Jesus are meant to join militias to fight and kill fellow American citizens? Followers of Jesus?

Followers of Jesus are meant to join militias to fight and kill fellow American citizens? Followers of Jesus?

Joyner’s battle cry to Christians is not compelling. There are many reasons why, more than can reasonably be assembled here, including the dubious, if not flawed, enlistment of biblical texts to support the call to arms.

But one particular text must be discussed, Luke 22:35-38. It is a brief word from Jesus to his closest followers about forsaking the violence of swordplay and instead follow his way of self-sacrificial love of others, including enemies. Strangely, Joyner flips this word about non-violent resistance around to mean the opposite of what Jesus meant. He lifts Jesus’ comment about a sword out of its context to justify today’s followers of Jesus heading out into the streets to fight a literal civil war in American cities. I want us to spend some time with that text here, as its meaning cannot be quickly understood. But when understood in both its immediate and larger contexts, Jesus’ words actually undermine the entire call to arms.

In the interest of full disclosure I should perhaps first say that I am offering this critical analysis of Joyner’s interpretation of the Luke text as someone who in principle is not opposed to what the New Testament identifies as the gift of prophecy, which, being part of “the way of love,” is meant to be spoken to people “for their strengthening, encouraging and comfort,” or, in short, for edifying the church (1 Corinthians 14:1-4).

I spent most the first fifteen years of my new life as a Christian in charismatic fellowships where, blessedly, mature expressions of the gifts of Spirit were operative, including that of prophecy. If someone stepped out of line, pastoral oversight appropriately addressed the situation. I personally benefited from this learning curve. Although I was eventually called to serve in (so-called) non-charismatic congregations about thirty years ago, I have enjoyed, benefited from, and been greatly thankful for being invited to minister countless times in charismatic fellowships since then. I try to be among them as best I can in the way of love, for their strengthening, encouraging, and comfort. (For the record, I am not a fan of the word “non-charismatic” applied to churches.)

If memory serves, I became acquainted with Joyner through two of his books in the mid-1980s, when I was still active full time within the charismatic tradition. (I don’t recall those books as objectionable in any fundamental sense within what I understood orthodox charismatic theology.) Around 1990, Joyner’s name dropped off my radar. Until the Bakker interview..

Now let’s get down to business. Here is a typical translation of Luke 22:35-38:

Then Jesus asked them, “When I sent you without purse, bag or sandals, did you lack anything?”

“Nothing,” they answered.

He said to them, “But now if you have a purse, take it, and also a bag; and if you don’t have a sword, sell your cloak and buy one. It is written: ‘And he was numbered with the transgressors’; and I tell you that this must be fulfilled in me. Yes, what is written about me is reaching its fulfillment.”

The disciples said, “See, Lord, here are two swords.”

“That is enough!” he replied.

During the interview with Bakker, Joyner places Jesus’ comment about the sword in the service of motivating today’s Christians to fight with weapons in a civil war in American cities. Joyner offers no explanation why he believes in this equivalency, which makes followers of Jesus instruments of violence and bloodshed. “We need to recognize the times, be prepared for them,” he explains, while confessing to viewers his worry that “God’s people” won’t become “part of the militia movements, the good militia” to fight the “bad people.” But “Jesus himself said there’s gonna be a time when you need to sell your coat and buy a sword. That was a physical weapon of their day. And we’re in that time here. We need to realize that.”

Bakker makes not a peep of protest to what Joyner is saying. Nevertheless, prophecies and interpretations of dreams and visions presented to the body of Christ as authoritative have to be tested, examined to determine if they are credible, authentic, or morally acceptable. After careful consideration of the Luke text, I believe that Joyner’s contention fails the test.

Jesus’ meaning about the sword, when considered in both its immediate and its related contexts, cannot be interpreted as call to arms. Instead, it undermines that call. Here’s why.

The immediate context is the Last Supper, where only Jesus’ twelve closest followers were assembled with him (until Judas leaves). The related contexts include events immediately following the Last Supper and also events in the three-year witness of Jesus’ life and ministry on the hillsides and in the towns of Galilee and Judea. Let’s start with the latter.

During those three exceptional years on the road with Jesus, the Twelve had witnessed Jesus’ self-sacrificing love of others, including of enemies. countless times. (The supreme expression being, “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.”) That is essential to who Jesus is. His ministry exemplifies it. In all sorts of relational encounters – whether someone needed counsel, or healing, or was up a tree – Jesus graced people’s lives with all sorts of various and diverse good. Day in and day out, the Twelve not only saw the beneficial effects of this on others, they even a hand at times in making it so.

But something else essential was also taking place. It wasn’t only through his acts of compassion – what the Old Testament person would call chesed (God’s loving-kindness) – but through his teaching that Jesus sought to instill the practice of self-sacrificing love of others into the lives of the Twelve. The fundamentals of that radical teaching are set forth in what we call the Sermon on the Mount, which arguably, can be understood as the Constitution for Jesus’ followers to live by. Their having been diligently taught for there solid years by their Rabbi, whose acts are consistent with what he taught, you can be forgiven for assuming that by the time of their last meal together the love of others would have become normative ministry for the Twelve. But our text in Luke reveals that a strong pull to take up arms had gotten hold of them. How so?

All four Gospels reveal that in the weeks leading up to the Last Supper Jesus knew he would soon be enduring a violent religious and political opposition that would put him to death, crucified as the archetypal act of self-sacrificing love. He also knew he was not going to resist this death with arms, even though he could command a legion of angels to fight for him (Matthew 26:53). With that understanding, let’s enter into some of the sights and sounds of the Last Supper.

All kinds of conversations and activities are going on among the thirteen men who have gathered privately to remember the Passover, a ritual meal that takes several hours. Jesus knows his arrest and violent death are imminent and that this would be their final meal together. In what has been called his farewell discourse, given to us in John chapters 14-17, Jesus offers many words of comfort and instruction for the eleven remaining disciples (Judas had left the meal early on, apparently; see John 13:21-30). At some point during those hours of communion and prayers in that room, Jesus detects a rising attitude of violence among his intimates. It needs to be addressed. So he brings up the subject of swords. He is, in effect, wanting them to know that although things are going to be different for them after his death, his message is not changing. It is still the gospel. The good news. The redeeming love of God. And they are to preach it and live it after he is gone, just as they saw him doing, day in, day out.

Why, then, was Jesus telling them to go buy swords? The answer is, he wasn’t. The Luke text intends for us to understand that no one at the Last Supper slipped out of the room to buy a sword. They did not need to. Some had arrived carrying swords: Lord, we’ve got two swords right here, they tell Jesus, no need to go buy any. As if he hadn’t noticed. Of course Jesus saw their weapons. If you have dinner guests over and two of them are packing, you may not notice that, but you’re sure going to notice if they arrive armed with swords.

Why, then, was Jesus telling them to go buy swords? The answer is, he wasn’t. The Luke text intends for us to understand that no one at the Last Supper slipped out of the room to buy a sword. They did not need to. Some had arrived carrying swords: Lord, we’ve got two swords right here, they tell Jesus, no need to go buy any. As if he hadn’t noticed. Of course Jesus saw their weapons. If you have dinner guests over and two of them are packing, you may not notice that, but you’re sure going to notice if they arrive armed with swords.

What’s with the sword comment, then? The answer will emerge from clues in a few other scenes during this period. One is found in John’s Gospel (18:1-11), which describes a moment during Jesus’ arrest that identifies the bluntly outspoken Simon Peter as one of the two with a sword. The personal identification seems more than an aside. Not many days before the Last Supper, Jesus had revealed to the Twelve, in plain language, that he was going to get arrested, suffer, and die. Hearing that, (Simon) Peter tried to talk Jesus out of going the way of the Cross. For having that attitude, however, Peter got rebuked by Jesus in no uncertain terms. Then Jesus adds: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it” (Matthew 16:21-25). Here was yet another teaching moment from Jesus, seeking to instill in his followers a heart attitude of self-sacrificing love toward others, including enemies.

Did Peter take the hint? Apparently not. The arrest scene described in John’s Gospel seems to imply that Peter arrived at the Last Supper armed with a sword. Maybe he regularly carried that weapon. Maybe he was carrying it the day he rebuked Jesus for wanting to go the way of the Cross. The Gospels are silent on these matters.

Another clue to Jesus’ meaning about the sword is found in Matthew’s Gospel in a scene described after the Passover meal. Jesus takes his inner circle to the Mount of Olives, where he again explains that he is soon to die. This time, Peter does not try to talk Jesus out of going to the Cross. Instead, he declares that he has such steadfast loyalty to Jesus that he is prepared to die with him right then and there. “And all the other disciples said the same” thing (26:35).

How Jesus understood the implication of that ad hoc agreement among his inner circle is important. Under Roman law there would be no legal reason for Peter, or any of the Twelve, to have been in jeopardy of prison or capital punishment at his arrest unless they had broken the law, which they would have done had they brandished weapons and ended up killing people in the mob who had come to arrest Jesus. Now Jesus and his disciples would have been fully aware of this Roman law. Yet at some point during the Last Supper, the eleven remaining intimates let their emotions get the better of them, becoming really angry and motivated by a spirit of violence. By the end of the hours’-long meal and much back-and-forth conversation during the meal and on the heavy walk to the Mount of Olives, these good guys (now sans Judas) are locked and loaded and ready to fight the bad guys, intent on becoming a band of street fighting men, a militia for Jesus.

In other words, the weapons carried in to the Last Supper and then to Jesus’ arrest had a literal meaning for his disciples. The inner circle (sans Judas) will take up arms to fight, even kill if necessary, those who had come to arrest Jesus. They seem to think that’s a good thing. That it is what Jesus is calling them to do.

Jesus had just dedicated three years of his life as a crash course of instruction and training to equip his closest followers to follow his lead, the peaceful way of the gospel. No way he does want them to get arrested, tried, and executed for acts of violence. If they go that way, end of them, end of story. No Book of Acts. It is difficult to imagine how distressed Jesus must have become by their rising attitude of violence just then.

They want to go kill the bad guys? Really? We’ve just broken bread together for the last time. I’m going away. They’re meant to carry my message of love to others, including love of enemies, out into a violent world. Are they going to do that now? What is this spirit of armed resistance among them? They’ve brought swords and mean to use them. What’s up with these guys? That’s not the the message of the Cross. Why do I even bother?

It is not difficult to see why the inner circle held a literal meaning to the swords. Just as we today know what weapons are used for, they too had absorbed that meaning since childhood. By the time they had reached adulthood it had become a given in their worldviews. All around them, for all their lives, they saw Roman legionnaires carrying a gladius (short sword), a pilum (six-and-a-half-foot javelin), and sometimes a pugio (dagger). How often any of the Twelve saw these weapons used in violence, your guess is as good as mine. What does not need guessing is that the sight of these weapons, and a knowledge of what they were used for, was inescapable to anyone who lived in the Roman empire. Jesus alludes to that widespread understanding in an arrest scene described in Matthew, Mark, and Luke: “Am I leading a rebellion, that you have come out with swords and clubs to capture me?”

It is not difficult to see why the inner circle held a literal meaning to the swords. Just as we today know what weapons are used for, they too had absorbed that meaning since childhood. By the time they had reached adulthood it had become a given in their worldviews. All around them, for all their lives, they saw Roman legionnaires carrying a gladius (short sword), a pilum (six-and-a-half-foot javelin), and sometimes a pugio (dagger). How often any of the Twelve saw these weapons used in violence, your guess is as good as mine. What does not need guessing is that the sight of these weapons, and a knowledge of what they were used for, was inescapable to anyone who lived in the Roman empire. Jesus alludes to that widespread understanding in an arrest scene described in Matthew, Mark, and Luke: “Am I leading a rebellion, that you have come out with swords and clubs to capture me?”

Can there be any other that a lethal meaning to the swords carried by Jesus’ followers? Jesus is about to demonstrate love of enemy to the uttermost empathy. Yet his intimates have decided they will move in the opposite spirit. I offer that in the Luke text Jesus, through grim irony, gives the weapons another meaning. Consistent with his message and example of love of enemy Jesus eschews the literal meaning of the swords and instead gives them a symbolic meaning: the violence in heart that objects to love of enemy. Jesus, deeply trouble by their attitude, in effect bursts out with, I’ve had enough of this! Let’s just go!

Although that is not how any translation I’m familiar with “hears” the words of Luke 22:38, and though personally I am not partial to paraphrases, at least not for serious study of Scripture, I often benefit from the fresh insight that can be derived from them, such as from this language in The Passion: “The disciples told him, ‘Lord, we already have two swords!’ You still don’t understand,” Jesus responded; and this from The Message: “They said, ‘Look, Master, two swords!’ But he said, ‘Enough of that; no more sword talk!’”

Why no more sword talk? Because Jesus see that his followers are in jeopardy of unleashing violence. They haven’t gotten it through their thick heads that the way of the gospel is absolutely not the way of violence.

Yet even during the heat and fury of his arrest, Jesus has a last go at changing their minds. When a cadre of Jewish religious officials and a crowd of their supporters are about to arrest Jesus, Peter draws his sword and cuts off the ear of the high priest’s servant. Personalizing that violent act even more, John includes the servant’s name, Malchus. And to that violent act Jesus immediately responds with a twofold action whose meaning could not be clearer. First: his sharp rebuke to Peter – “No more of this!” “Put your sword back in its place, for all who draw the sword will die by the sword.” Second: the healing of the servant’s ear (Luke 22:51; Matthew 26:52; John 18:11). Here we see Jesus, the quintessence of love toward others, even to those in the mob come to arrest him, acting consistent with his cry of deep frustration, recorded in Luke 22:38. He has had enough. Off he goes to his crucifixion.

This was not the only time Jesus laid a stern rebuke on members of the Twelve for being motivated by a violent spirit. Earlier in Jesus’ ministry, the brothers James and John (the Sons of Thunder) cited an incident from the life of the prophet Elijah (2 Kings 1:12) to try to justify calling fire down from heaven to destroy an entire village. But Jesus “rebuked them and said, ‘You know not what manner of spirit you are of. For the Son of Man [has] not come to destroy lives but to save them’” (Luke 9:51-56).

Isaiah chapter 53 indicates that the Messiah will be the suffering not the military servant. Sure, followers of Jesus may and do face violent opposition at times and even death. If that hour arrives, let us come boldly before the Throne of Grace for divine help in our time of deepest need, to cry out for the grace of sacrificial love toward our persecutors.

Isaiah chapter 53 indicates that the Messiah will be the suffering not the military servant. Sure, followers of Jesus may and do face violent opposition at times and even death. If that hour arrives, let us come boldly before the Throne of Grace for divine help in our time of deepest need, to cry out for the grace of sacrificial love toward our persecutors.

Things are going to be different, now, Jesus in effect said to his disciples. Times are changing. I’m going away. But my message to you to love others is not changing, even when you are threatened with violent religious or political opposition. You have not been called by me to take up arms but to open arms of love. And this you will do through the peaceable gospel in power of the Holy Spirit. For I have come into the world not to add violence to violence but to subtract violence from the world.

Jesus’ intimates eventually got the message. The love that Jesus had toward others became his followers normative witness after his death and resurrection and the Holy Spirit, who testifies about Jesus (John 15:26), took up residence in their hearts. And thus we do have the Book of Acts. It is noteworthy, is it not, that in no place in the Book of Acts, or in any other Epistle, does an Apostle or any other follower of Jesus take up arms, even when facing violent social, political, or religious opposition. In other words, the Last Supper was not just meaningful to Jesus but also to his followers. As the Last Supper represented to them how Jesus had lived, it gave them direction as to how they were to live.

And live that way they did, not perfectly of course, but they were continually reminded about what was at stake through their regular practice of the Lord’s Supper, first mentioned in chapter eleven of First Corinthians. What was at stake was their faithful communion, day in, day out, in the church and in public, with the meaning and message of the Last Supper. And the consequences of maligning that knowledge.

Today we have what we call the Lord’s Supper, which we partake of in remembrance of the Last Supper. (It may known by other names, such as the Lord’s Table, the Breaking of Bread, the Eucharist, Communion.) What are we today remembering? What are we partaking of? What are we agreeing to when we receive the bread and the wine? Of what is it a symbol to us today? For the earliest followers of Jesus it was indeed remembrance of Jesus’ sacrificial death. But it was also a symbolic reminder as to how they were to live everyday, and not just toward some people but to all people, and not just in one’s family or church but in all areas of life. Let us ask ourselves how we’re doing at this. In humble prayer, let us ask the Lord how we’re doing.

To partake of the Lord’s Supper in remembrance of so great a salvation that Jesus Christ has accomplished for us sinners is a great thing. But it is not the only thing. Perhaps every time we partake of the bread and the wine we are also meant to remember that we are no longer our own, that now we live for Another, for the One who himself lived for others. Perhaps each time we partake we are giving our assent anew to follow Jesus, to live in the world as he lived in the world, serving others in denial of self. Perhaps every time we partake we are renewing our commitment to be living epistles who demonstrate to whosoever as best we can, including to enemies, the grace-giving love of Jesus, in small things and large, in any state of affairs, including socially and politically. If it is true that our partaking of the bread and the wine commits us to following Jesus, to live as he lived, it would make it a serious matter indeed to partake unworthily (1 Corinthians 11:27-32).

Will we not be judged as bearing false witness to Christ’s love of others if we if we partake of the Lord’s Supper one day and take up arms the next?

There is another sword spoken of in the New Testament. It is not the sword of a violent, murderous world. It is “the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God” (Ephesians 6:17), which we are called to study and rightly divide (2 Timothy 2:15). And “the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword…, it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart” (Hebrews 4:12). These are exhortations to open our hearts to let the word of God search and refine them in utterly personal ways, including how we interpret the meaning of Luke 22:35-38, especially in the heat and fury of our national moments.

Choosing between the two perennial traditions – the one violent, the other forbidding it – is always being placed before followers of Jesus. Will we walk humbly in the grace and power of the Holy Spirit into the pages of our own Book of Acts? Or will we take up arms to participate in the kind of violence that killed our Lord?

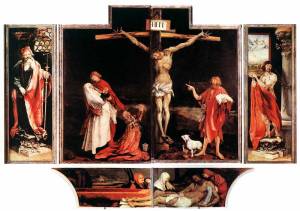

Top photo: Sword sculpture photo by Andrea Brizzi. Lower photo: Grunewald’s-Isenheim Altarpiece. Star flower and two paths images courtesy of Creative Commons.

©2020 by Charles Strohmer